The Slocan Valley – Our History

by Katherine Gordon

Today’s communities of the Slocan Valley are barely one hundred years old, and yet the Slocan has seen some of Canada’s most dramatic and interesting history.

Several thousand years ago, Aboriginal people occupied the valley, using its resources for food and shelter. Archaeological sites are scattered along the length of Slocan River and there are some beautiful and well preserved rock art pictures on the western cliffs of Slocan Lake. There are members of the Sinixt Nation living in the Valley today, and the Ktunaxa Nation are discussing areas in the Slocan Valley as part of their contemporary treaty talks. But until as late as 1890, almost no-one else had even seen the Slocan Valley, let alone knew about it.

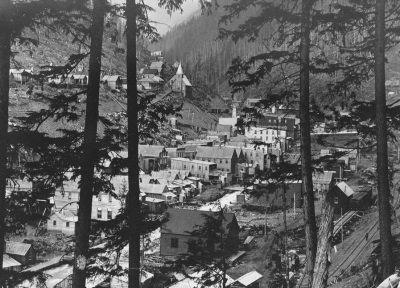

A discovery in the early 1890s would change all that forever. Rich silver-lead ore was found near Sandon, and thousands of prospectors and fortune hunters poured into the area, lending it its well worn name “The Silvery Slocan.” Mining created towns like Sandon – styling itself the “Paris of the West” – New Denver, and Slocan City. Several smaller settlements sprang up along what is now Highway 31A between New Denver and Kaslo. Competing railway companies rapidly built lines into the mining camps. For a time it seemed the prosperity would last forever. The population of Slocan City and Sandon were in the thousands and the champagne flowed liberally. But it was a short-lived phase: by 1910 the fortunes of the mining towns had declined to almost nothing. Many of them vanished altogether. One or two, like New Denver and Silverton, pegged their future on agriculture and recreation instead; and Sandon became a veritable “ghost town,” with its population sinking to as low as one person in the 1980s.

A discovery in the early 1890s would change all that forever. Rich silver-lead ore was found near Sandon, and thousands of prospectors and fortune hunters poured into the area, lending it its well worn name “The Silvery Slocan.” Mining created towns like Sandon – styling itself the “Paris of the West” – New Denver, and Slocan City. Several smaller settlements sprang up along what is now Highway 31A between New Denver and Kaslo. Competing railway companies rapidly built lines into the mining camps. For a time it seemed the prosperity would last forever. The population of Slocan City and Sandon were in the thousands and the champagne flowed liberally. But it was a short-lived phase: by 1910 the fortunes of the mining towns had declined to almost nothing. Many of them vanished altogether. One or two, like New Denver and Silverton, pegged their future on agriculture and recreation instead; and Sandon became a veritable “ghost town,” with its population sinking to as low as one person in the 1980s.

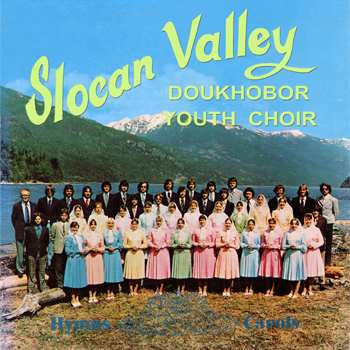

The south end of the valley was largely settled by farmers, the most famous of which were the Russian Doukhobors who came west to British Columbia in 1908. The Doukhobors were escaping religious persecution in their homeland and the Slocan seemed the ideal place to settle and practice their communal lifestyle. Unfortunately, clashes with the government regarding compliance with administrative regulations and taxation requirements would see the Doukhobors lose almost all of their communal lands. A series of protests by some Doukhobors sparked severe government retaliation, and even resulted in the enforced separation of parents from children for a number of years; a matter that the government is now making attempts to redress.

There are many Doukhobors living in the Slocan today. The rich culture of agriculture, spirituality, and communal cooperation had become part of the way of life in the valley for all of its residents and the Doukhobor Museum at Castlegar is carefully preserving and recording the history and traditions of the Doukhobors.

Following in the footsteps of the Doukhobors was a brief rush of British immigrants, lured to the West Kootenay on the promise of “Grow apples and grow rich in Appledale!” Buying lots sight unseen, they were middle class “genteel” men and women who came to the valley with visions of tidy apple orchards and white picket fences – only to find steeply sloping sections covered in salal and huge trees. Many of them fled further west to Vancouver but a few stayed to persevere. Today only the last lingering blossoming fruit trees in the spring reminds the passerby of the valiant efforts of those farmers – the weather and the isolation of the valley would ultimately defeat them.

The 1940s saw yet another cultural addition to the valley – the result of a deplorable decision on the part of government, but one which would once again enrich the Slocan permanently. During World War Two, Canada’s citizens of Japanese descent living on the west coast were forced to leave their homes and possessions and were interned in camps until the war was over. Most of those camps were in the north end of the Slocan Valley. David Suzuki was interned as a little boy in the Slocan camp. The remnants of the New Denver camp remain visible today, as private family homes in the southern section of New Denver known as “The Orchard.”

Many of the Japanese stayed in the Slocan after the war was over – partly because they had no homes to return to on the coast, and partly because they had fallen in love with it. Their memories are preserved at the Nikkei Memorial Internment Centre in New Denver.

The 1970s saw another influx of immigrants. This time many of them were Americans fleeing the Vietnam War or the American system, but there were also many Canadians heading west from the big eastern cities and the prairies. Communal living and agricultural “back to the land” self-sustenance became popular all over again. This period also saw the rise of the burgeoning arts community for which the Slocan has now become so well known – ranging from theatre to textiles to canvas, and much more.

The Slocan’s more recent history has seen it continue to blend its diverse cultures into a way of life that continues to be challenging, adventurous, and incredibly rich. The people of the Slocan are no longer watching history happen to them: they are making their history for themselves.

Katherine Gordon is the author of The Slocan: Portrait of a Valley (Sono Nis Press, 2004).